Why we need nutritional & functional medicine?

Dato’ Sri Steve Yap SSAP, MSc (Oxon), MS (USF), DMedSc (UCG), FICT, FAARFM, FNMedP

President, The Association of Nutritional & Functional Medicine Practitioners Malaysia (www.anfmp.org.my)

“The doctor of the future will give no medicine, but will interest his patients in the care of the human frame, in diet, and in the cause and prevention of disease.” (Thomas Edison)

The Background

While numerous technologies have advanced exponentially, the application of nutritional medicine in addressing dietary/lifestyle-linked diseases remains in the “Stone Age” era due largely to extremely low research funding on complementary medicine [1] . Widespread consumption of genetically-modified food items, use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, poor food harvesting and storing methods, nutrient-destroying food processing, and cooking under high temperatures have all adversely affected our nutrient intake. Medical and health schools pay lip service to these issues despite extensive research in nutrigenomics [2] and the W.H.O. call for reduction in premature death from dietary/lifestyle-related chronic health disorders (non-communicable diseases or NCDs).

The current annual premature deaths from chronic disorders are estimated at more than 40 million [3] with over 85% of these coming from low-and middle-income countries such as Malaysia. For the past decade, the WHO Centre for Self-Care has emphasized reversible dietary/lifestyle habits as contributing to this sad state of affair. Indeed, NCDs in Malaysia are becoming an epidemic [4]. Besides having the most obese population in Eastern Asia [5], the numbers for NCDs are expected to rise resulting in substantial portion of the national health budget being spent on treatment of symptoms as a means to improving the patients’ quality of life (QoL). Although studies have shown that most metabolic disorders are reversible by dietary and lifestyle modifications [6], no major attempts are made at governmental and professional levels to promote reversal of these disorders using evidence-based nutritional/functional medicine. Despite well-established mainstream medical practice guidelines having uniformly calling for lifestyle changes as the first line of metabolic therapy [7], studies have shown that physicians are often unable to follow these recommendations [8]. Physicians have often cited inadequate confidence and lack of technical knowledge as their major obstacles to effectively counsel patients on dietary/ lifestyle interventions [9]. Clearly, the provision for nutrition education in medical schools remains inadequate [10]. The practice of evidence-based nutritional/ functional medicine can make a substantial contribution to the management of these leading killers of mankind.

Allopathic physicians have made outstanding contribution to the management of emergency (acute) and trauma medicine. However, orthodox treatment model of “waiting for our body to break down before attempting to fix it” may be unacceptable to many in terms of the huge economic costs to the nation as well as the cost of human suffering. In the coming post-COVID era, the practice of preventive medicine is poised to make dramatic transformation. A rapidly growing middle-class, educated, and IT-literate is expected to drive demand for, among others, medical treatments that inflict fewer or no harmful side effects, a more personalised health partnership between patients and practitioners in resolving chronic health issues, and access to a much less intrusive but evidence-based medicine which is reasonably priced. IT and AI powered by 5G will likely accelerate individualised medicine in the coming decades.

It is now widely recognised that the strongest defense system against diseases is our bodies’ own natural antioxidants and immune system promoted by healthful dietary/lifestyle habits.

Prevalent use of nutritional treatment

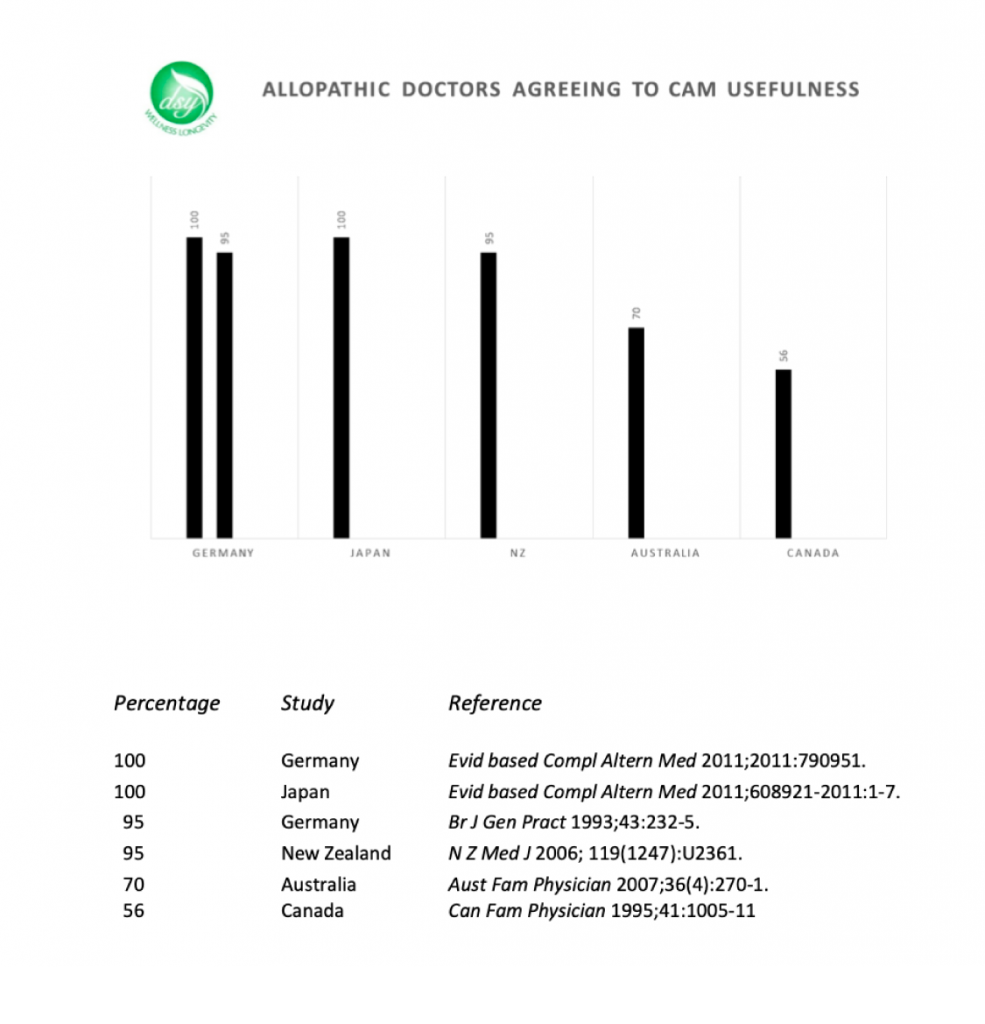

In Britain, it is estimated that more than half of its population visits complementary medical practitioners in the past year [11] with average referral rate of 39% by physicians to complementary therapies [12]. In Germany, the referral rate is significantly higher.

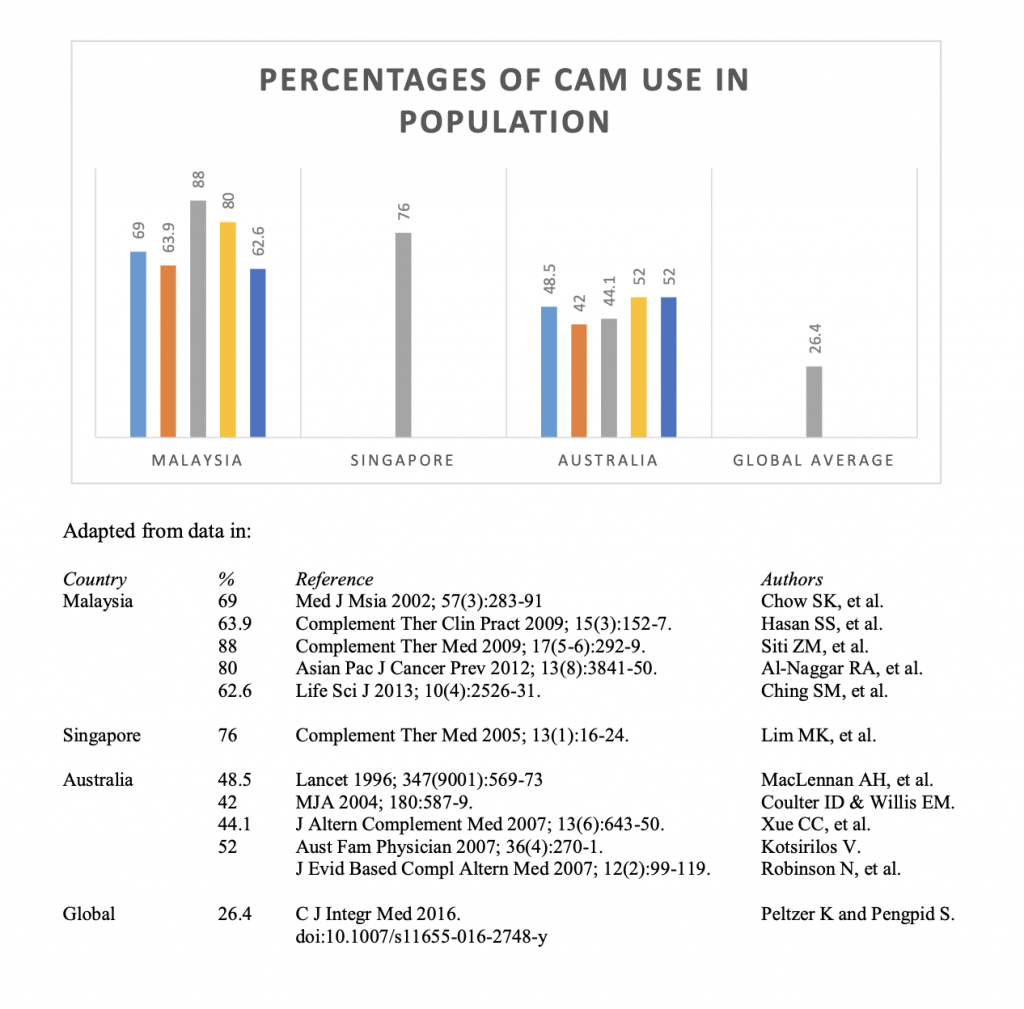

Local survey by Chow et al. (2002) [13] showed some 69% of patients consuming nutritional supplements with being female and possession of higher education as major predictors of their use. Later research by Hasan et al. (2009) [14] and by Ching et al. (2013) [15] both showed an average 63% utilisation rate especially among patients with chronic diseases.

Populations in South-East Asia countries have a strong tradition in the use of whole food, food extracts, spices, and/or herbs as ‘medicine’. Siti et al. (2009) [16] found these biological-based therapies were used to treat health disorders (88%) and for health maintenance (87.3%).

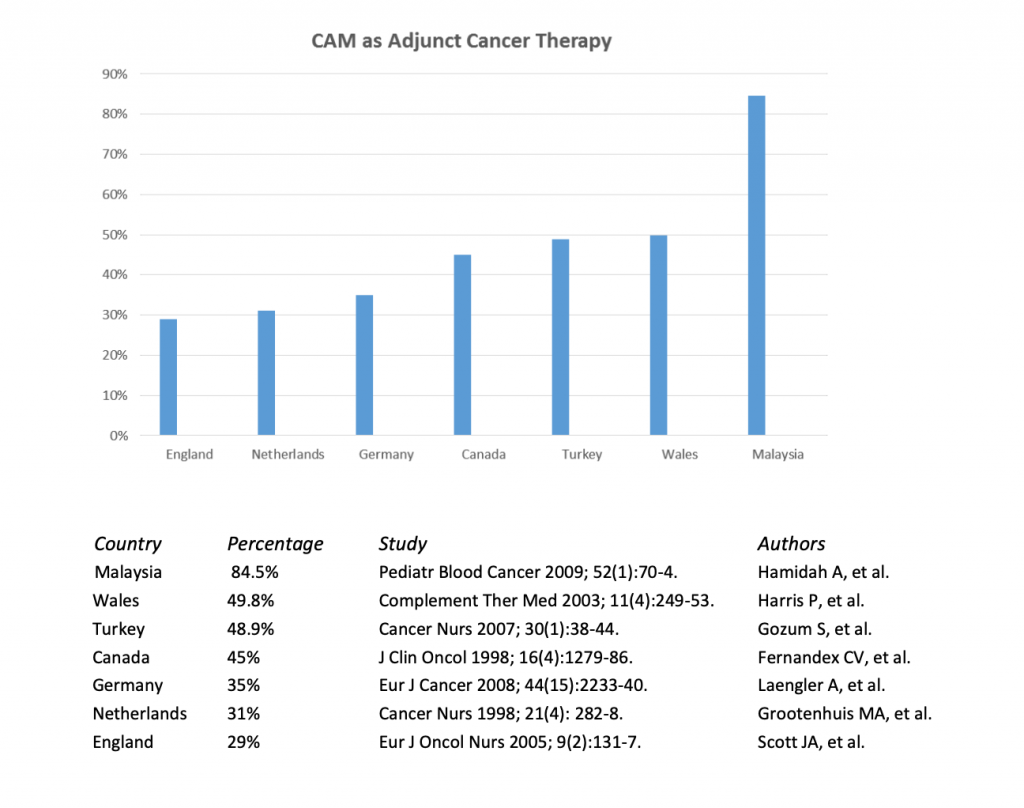

Arguably, the most widespread use of traditional and complementary medicine (known as ‘T&CM’ locally or ‘CAM’ in overseas) and nutritional medicine in particular is as an adjunct treatment for malignancy [17].

Nature of Nutritional & Functional Medicine

Nutritional Medicine, as a modality within complementary medicine, is officially defined by the Constitution of the Association of Nutritional and Functional Medicine Practitioners Malaysia as “the application of cutting-edge health/medical science and evidence-based nutrients, phytochemicals, nutraceuticals to enable patients to maximise their health potential including treating, controlling and preventing chronic metabolic health disorders which protocols can impact on their hormonal, neurological and/or immune functions.” This definition by the Nutritional Therapy Council, United Kingdom (2006) was adopted to reflect a non-invasive clinical practice of a similar nature.

Chronic health disorders almost always preceded by lengthy period of declining function in one or more key bodily functions. These dysfunctions are, generally, the consequence of lifelong interactions amongst environmental factors, dietary/lifestyles issues, and genetic predisposition.

Nutritional medicine seeks to address the known (researched) cause(s) of a chronic illness/disease and then recommends a treatment protocol that is drug free. Usually, this involves relying on results from mainstream diagnosis and other highly sophisticated non-invasive diagnostic tests available to modern science, designing a diet that matches the patients’ nutritional/physiological needs, recommending modifications in patient’s lifestyle, and supplementing patients with evidence-based macro- and/or micronutrients targeted at specific chronic health issues.

Nutrients such as vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B6, B12, D and K as well as extracts from edible plants such as chlorophyll, carotenoids, flavins, and artemisinin were the basis of Nobel Prizes in Medicine or Physiology or Chemistry since 1915. There are tens of thousands of micro- and phytonutrients from vegetable, spice, fruit, seafood, mushroom, and other plant sources already known to medical science. Indeed, more than 80% of the world rely on them as part of their primary healthcare [18].

According to the US Institute for Functional Medicine (2010), FM involves “identifying and following biomarkers of function that can be used as indicators of the onset of disease, and also markers of the success of interventions, is an extremely important activity of functional medicine.”

Preventive medicine is the hallmark of nutritional/functional medicine. It can take years or even decades to develop chronic health problems, which their known causes are addressed and mapped out well before they reach their critical or even ‘terminal’ stages. This is especially true in the case of prevention and treatment for the potentially fatal NCDs as listed by the WHO. However, in any life-threatening condition, NFM practitioner would refer the patient to the nearest hospital/clinic for acute conditions to be treated. Since the 11th Malaysian Health Plan (2016-2020), complementary medicine was to serve all levels of national healthcare to pave the way for eventual introduction of “integrated medicine”. The gradual adoption of traditional and complementary medicine (CAM) is a global phenomenon as evidenced by this Chart:

Evidence-based Nutritional & Functional Medicine

The Father of Western Medicine, the late Sir William Osler pointed out that “Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability”. Historically the basis of diagnosis was almost purely clinical authority and not necessarily on scientific criteria [19]. Physicians have depended on tests, treatments and ad hoc rules of thumb (heuristics) to guide them [20]. Clinical practice was based on their “art of medicine” gained from experience and is still true today [21]. However, almost all aspects of medical practice is in constant and accelerating change [22].

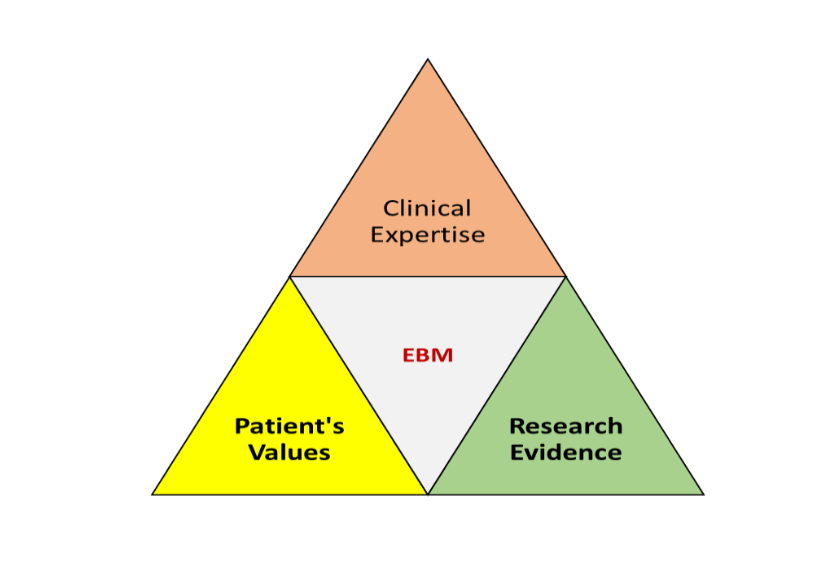

Sackett et al. (1996) [23] defined evidence-based medicine as “…the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical experience with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” Since then it has become apparent that numerous non-clinical factors could influence on and would inform clinical decision-making [24] . Furthermore, “best evidence” for allopathic medicine can be different for complementary medicine. To be competent in patient care, practising evidence-based medicine can be a “process of life-long, self-directed learning in which caring for patients creates the need for clinically important information about diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, and other clinical and health care issues.” [25].

Depending on systematic reviews or meta-analyses to inform clinical decisions may only be partly correct since more than 40% of the highly cited original clinical research studies could not be replicated [26]. There might even be a strong cultural dimension to the application of evidence-based practice [27]. Besides, case reports/series offer valid evidence for use in complementary medicine. Ernst (1998) [28] even proposed the use of single-case study as a useful research tool for investigating a very specific research question framed in relation to an individual patient. Today, the globally-recognised dimensions of evidence-based practice consists of three distinct components:

Despite exponential growth in evidence-based practices [29], a local survey study found most primary care physicians have yet to adopt such practices [30].

Reasons why Patients choose Complementary Therapies

Based on published research studies, these are some of the common reasons given:

- Patients’ desire for a more holistic healthcare as part of their healing experience [31];

- Patients’ belief in lifestyle-aspects of their chronic diseases [32] ;

- Patients’ belief in the “psychological factors” inherent in their chronic illnesses [33];

- Patients’ desire for greater control over the management of their own chronic conditions [34];

- Patients’ belief in their innate abilities to heal with help from natural remedies [35];

- Patients’ belief in the effectiveness of complementary medicine based on past experiences [36];

- Complementary therapists having “better bed-side manners” [37];

- Experience of improved QoL and overall health when using complementary therapies with conventional treatment [38];

- Dissatisfaction over mainstream treatments [39];

- Scepticism over efficacy of present mainstream treatments [40]; and

- Concerns over safety and side-effects of conventional treatment [41].

GLOBAL MEDICAL WELLNESS INDUSTRY

Besides traditional and complementary medicine markets worth more than US$400 billion, personalised and preventative healthcare incorporating nutritional/functional medicine enjoy rapid growth in the past two decades and these sectors are likely to continue flourishing in coming the post-COVID era. The Global Wellness Institute reported the 2020 wellness market as follows:

Nutrients as basis for Nobel Prizes in Medicine & Physiology, and Chemistry

It is argued that the prescriptions using nutrients such as vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B6, B12, D and K as well as plant extracts such as chlorophyll, carotenoids, flavins, and artemisinin require hardly any further large-scale testing using RCTs for them to be “evidence-based”. These nutrients and phyto-nutrients were the basis of extensive research that led to the award of Nobel Prizes since 1915. Conflicts of (commercial) interest and publication biases have no place in modern healthcare where patients are becoming increasing educated and IT-literate. Thanks to rapid development in AI and 5G, healthcare in the coming decades will be highly individualised as envisaged by the then JAMA Working Committee (1992) in order to suit the exact physiological needs of patients seeking natural preventive medicine for managing their chronic health disorders.

What does the ANFMP Membership Qualifying Route entail?

Its practising membership category is opened to medical practitioners/healthcare professionals, conventional or otherwise, who have completed an academic programme approved by its Academic/Membership Committees. Graduates with non-medical science related degrees are advised to complete the Associateship Programme (a Professional Certificate in Nutritional Therapy awarded by Universiti Malaya Centre for Continuing Education) prior to transfer to the professional programmes, which carry tertiary awards from another MOE-registered and State-owned University. Please liaise with its Honorary Secretary for more details.

ANFMP Constitution states that a practitioner shall hold Ordinary Membership and has successfully completed both (a) the prescribed academic curriculum, examinations and coursework projects in force at time of application for a Membership Certificate with practicing rights; and (b) the Clinical Year, which is exempted for medical doctors.

The “Clinical Year” shall mean:

(i) Prior to official listing by the Traditional and Complementary Council, the Association’s Committee approved training under the supervision of a senior member in clinical practice; and

(ii) Subsequent upon listing by the Council, the regulations/rules laid down by the T&CM Council pertaining to clinical or practical training shall prevail.

Besides possessing a professional indemnity insurance cover, practitioners shall comply with Association’s rules pertaining to prescription of nutraceuticals and on adopting continuing professional development programme.

According to the ANFMP Constitution, qualifications obtained from these organisations or institutions would not in themselves be sufficient to meet the academic requirements for admission to ANFMP Ordinary Membership:

- Royal Institute of Public Health;

- Royal Society for Promotion of Health;

- Institute of Food Sciences & Technology;

- ITEC (UK) Diploma in Nutritional Therapy;

- City & Guilds, London;

- The Nutrition Society;

- Anti-Ageing Societies;

- Integrated medicine societies;

- Diploma in Nutritional/Functional Medicine accredited by non-JPA recognised overseas universities;

- University or college awards on Nutrition or Dietary Planning/Counselling;

- Degree in nutritional therapy awarded by non-JPA recognised university overseas; or

- Post-graduate research-based degree on nutritional medicine/therapy.

These candidates may be admitted to Associate membership and pursue professional training to full (ordinary) membership by completing the prescribed professional upgrading programme (PUP).

An outline of the academic curriculum for ANFMP’s PUP can be downloaded from www.anfmp.org.my. It covers the key subject matters for which patients with chronic disorders seek assistance from nutritional/functional medicine practitioners. Teaching by the School of Complementary & Traditional Medicine (SCOTMED) is validated, and academic awards offered, by the University College of Yayasan Pahang. Academically, there are three distinct areas to be completed, namely the core, specialist, and professional practice modules.

What’s the Status of this Profession in Malaysia?

With the gradual implementation of provisions within the Traditional and Complementary Medicine Act 2016, and the pending application to the T&CM Council for listing of Nutritional/Functional Medicine, it is anticipated that this modality is likely to be incorporated into the proposed integrated healthcare system of the future [42] when there are sizeable number of qualified practitioners available for hire by the public sector. Currently, this modality serves the private sector healthcare industry. The integration of nutritional/functional medicine into healthcare system will be accelerated if more mainstream medical doctors are trained to practice this highly evidence-based modality.

[1] Ernst E. Only 0.08% of funding for research in NHS goes to complementary medicine. BMJ 1996; 313:882.

[2] Ordovas JM, Ferguson LR, Tai ES, et al. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ 2018; 361:K2173.

[3] Word Health Organisation. Noncommunicable Diseases. 13 April 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases#:~:text=Key%20facts,%2D%20and%20middle%2Dincome%20countries

[4] Ariffin F, Ramli AS, Daud MH, et al. Feasibility of implementing chronic care model in the Malaysian public primary care setting. Med J Malaysia 2017; 72(2): 106-12.

[5] Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 2014; 384:766-81.

[6] Forouhi NG, Misra A, Mohan V, et al. Dietary and nutritional approaches for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. BMJ 2018; 361: k2234.

[7] American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care 2010; 33 :(suppl 1) S11-S6120042772.

[8] Lianov L, Johnson M. Physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine. JAMA 2010; 304(2): 202-3.

[9] Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, et al. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med 2004; 79: 156-61.

[10] Adams KM, Lindell KC, Kohlmeier M, et al. Status of nutrition education in medical schools. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83(4): 941-4.

[11] Thomas K, Coleman P. Use of complementary or alternative medicine in a general population in Great Britain. Results from the National Omnibus survey. J Public Health 2004; 26(2):152-7.

[12] Posadzki P, Alotaibi A, Ernst E. Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by physicians in the UK: a systematic review of surveys. Clin Med (Lond) 2012; 12(6):505-12.

[13] Chow SK, Yeap SS, Goh EM, et al. Traditional medicine and food supplements in rheumatic diseases. Med J Msia 2002;57(3):283-91.

[14] Hasan SS, Ahmed SI, Nukhari NI et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with chronic diseases at outpatient clinics. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2009; 15(3):152-7.

[15] Ching SM, Zakaria ZA, Paimin F, et al. Complementary alternative medicine use among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the primary care setting: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;26(130:148.

[16] Siti ZM, Tahir A, Farah AI, et al. Use of traditional and complementary medicine in Malaysia: a baseline study. Complement Ther Med 2009; 17(5-6):292-9.

[17] Connor S. Science Editor. Glaxo chief: Our drugs do not work on most patients. 8 December 2003, The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/glaxo-chief-our-drugs-do-not-work-on-most-patients-5508670.html

[18] Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Fromt Pharmacol 2013;4:177.

[19] Feinstein AR, Massa R. Prognostic significance of valvular involvement in acute rheumatic fever. NEJM 1959; 260:1001–7.

[20] McDonald CJ. Medical Heuristics: The Silent Adjudicators of Clinical Practice. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124(1): 56-62.

[21] Verhoef MJ, Sutherland LR. Alternative medicine and general practitioners. Can Fam Physician 1995; 41:1005-11

[22] Guyatt GH, Rennie D. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature. JAMA 1993; 270(17):2096-7.

[23] Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996; 312 (7023):71–2.

[24] Hajjaj FM, Salek MS, Basra MKA, et al. Non-clinical influences on clinical decision-making: a major challenge to evidence-based practice. J R Soc Med 2010; 103(5):178-87.

[25] Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992; 268(17):2420–5.

[26] Ioannidis JPA. Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited clinical research. JAMA 2005; 294(2):218-28.

[27] Yokota T, Kojima S, Yamauchi H, et al. Evidence-based medicine in Japan. Lancet 2005; 366(9480): 122.

[28] Ernst E. Single-case studies in complementary/alternative medicine research. Compl Ther Med 1998; 6(2):75-8.

[29] Straus SE. What’s the E in EBM? BMJ 2004;328(7439):535-6.

[30] Chan GC and CL Teng. Primary care doctors’ perceptions towards evidence-based medicine in Melaka State: a questionnaire study. Med J Malaysia 2005;60(2):130-3.

[31] Sointu E. Complementary and alternative medicines, embodied subjectivity and experiences of healing. Health (Lond) 2013; 17(5):530-45.

[32] Furnham A, Bhagrath R. A comparison of health beliefs and behaviours of clients of orthodox and complementary medicine. Br J Clin Psychol 1993; 32(Pt 2):237-46.

[33] Vincent C, Furnham A, Willsmore M. The perceived efficacy of complementary and orthodox medicine in complementary and general practice patients. Health Educ Res 1995; 10(4):395-405.

[34] Jones I, Britten N. Why do some patients not cash their prescriptions? Br J Gen Pract 1998; 48(426):903-5.

[35] Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. A Systematic review of beliefs involved in the use of complementary and alternative medicine. J Health Psychol 2007; 12(6):851-67.

[36] Furnham A, Kirkcaldy B. The health beliefs and behaviours of orthodox and complementary medicine clients. Br J Clin Psychol 1996; 35(Pt 1):49-61.

[37] Ernst E, Resch KL, Hill S. Do complementary practitioners have a better bedside manner than physicians? J R Soc Med 1997; 90:118-9.

[38] Hasan SS, Loon WCW, Ahmadi K, et al. Reasons, perceived efficacy and factors associated with complementary and alternative medicine use among Malaysian patients with diabetes mellitus. Br J Diab Vasc Dis 2011;11(2):92-8.

[39] Sugimoto A, Furnham A. The health beliefs, experiences and personality of Japanese patients seeking orthodox vs complementary medicine. Compl Ther Med 1999; 7(3): 175-82.

[40] Vincent C, Furnham A, Willsmore M. The perceived efficacy of complementary and orthodox medicine in complementary and general practice patients. Health Educ Res 1995; 10(4):395-405.

[41] White PT. What can general practice learn from complementary medicine? Br J Gen Pract 2000; 50:821-3.

[42] Bernama. Health Ministry to expand Traditional and Complementary Medicine service nationwide. 09 Jan 2020.

Dato’ Sri Steve Yap holds a Masters’ in Evidence-Based Healthcare (Systematic Review) from the Oxford University’s Graduate School of Evidence-based Medicine & Research where he researched on dietary/lifestyle interventions for individuals carrying the ApoE allele genotype. He also graduated with a Masters’ in Metabolic and Nutritional Medicine (GPA3.93/4.00) from the University of South Florida’s Morsani College of Medicine, and completed a Fellowship in Integrative Cancer Therapies (USA), a Fellowship in Anti-Aging, Regenerative & Functional Medicine (USA), and board certification in both Nutritional Medicine (Distinction) and Anti-Ageing Medicine (Distinction) from WOSIAM Paris. For a decade, he served on the Experts’ Panels for nutritional therapy, anti-ageing medicine and complementary medicine for the Malaysian Quality Agency, Ministry of Higher Education as well as a current member of the Traditional & Complementary Medical Council established under the T&CM Act 2016. He is adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Science, Engineering & Agrotechnology, University College of Yayasan Pahang.

Dato’ Sri has been in nutritional/functional medical practice for the past 19 years. Views expressed are his own and do not necessarily represent those of the various technical committees on which he has served at MOH and MOE. This article is for information and education only. The author can be contacted at: dsy@dsywellness.com

8 October, 2022